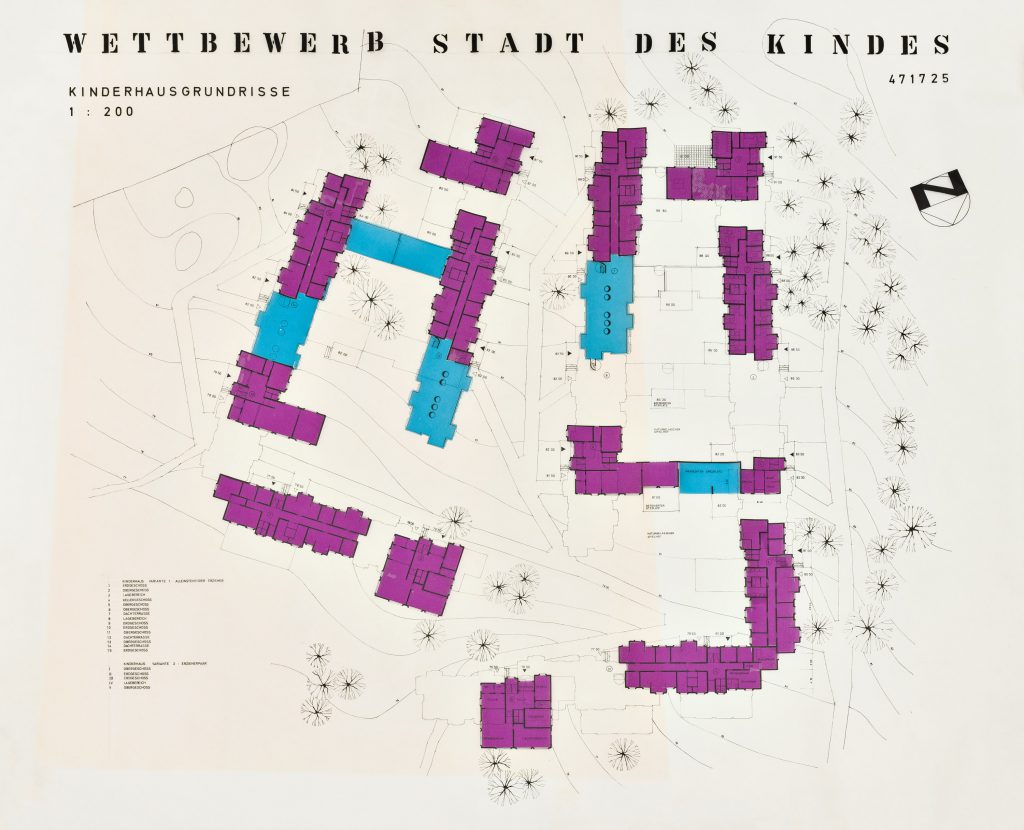

Edith Lassmann, Wettbewerb Stadt des Kindes, Kinderhausgrundrisse, 1968

© Architekturzentrum Wien, Collection

"Well, the jury had made its decision and it was binding. When they realised whose design they had decided upon they took over a month to ring me."1)

In 1950, the jury, consisting of a series of renowned architects around Erich Boltenstern, would never have thought it could happen, not in their wildest dreams. To have selected, of all people, the only woman to to participate in the competition for the further planning of the prestigious reconstruction project at Kaprun Tauern power station.2) Not only were women architects rare at the time, but the first 30-year-old had been commissioned to design the power station in one of the largest hydro-electric power plants in Europe, which caused a furore of indignation among the majority of male architects. The construction of the hydro-electric power plant had commenced in 1938 under the Nazi regime with the use of prisoners of war and forced labour, although work ceased following the end of the war. At the end of the war it was considered one of the core identity promoting projects in the reconstruction of Germany.3) Lassmann’s impact in the rough-and-ready world of power plant construction turned out to be more than problematic. She was not allowed to eat with the men in the canteen, she had to bring her own food. When she started work there, she countered a shouted “Listen, doll!” with “I’m nobody’s doll!”. Through her undisputed technical know-how, she gradually gained the respect of the construction workers on site. Her success at Kaprun brought Lassmann further commissions for a range of power plants.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Republic of Austria, in 1968 the City of Vienna decided to establish a City of the Child. Among the 12 participants in the invited entry competition, Edith Lassmann was once again the only woman — along with Traude Windbrechtinger, who worked with her husband Wolfgang in a joint architecture office. The extensive spatial programme with residential units, a leisure centre with swimming pool, a library, a gymnasium, a festival hall, outdoor sports facilities, children’s playground etc. was explicitly intended to provide local children with a connection to the outside world. Lassmann came in second, behind Anton Schweighofer, although her City of the Child would have fitted completely differently into the 48,000 square metre site in Penzing, on the edge of the Vienna Woods: While Schweighofer’s realised design was conceived as a linear ideal city with compact building volumes and a lively residential street, Lassmann’s cluster strategy was oriented towards the structure of an evolved city. Housing, open spaces and public buildings alternate and form a loosened-up layout, as can be seen on the plans in the Az W collection since 2016.

1 Erika Thurner: Nationale Identitäten und Geschlecht in Österreich nach 1945, Vienna 2000, quoted in: Alexandra KRAUS: ‘Zum Leben und Werk der Architektin Edith Lassmann (1920–2007)’, Graduate thesis, TU Wien 2018 p.44. Here, in Translation.

2 In concrete terms, the brief was for the planning and design of the Limberg dam crest and the Oberstufe powerhouse.

3 Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, ‘Edith Lassmann 1920–2007’, in: Ingrid Holzschuh, Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, Pionierinnen der Wiener Architektur, Basel 2022, p.76.